Buying my home is a complete financial folly, and against all my financial principles. I can only justify it because I can afford this folly, thanks to the high yields I have on investment properties overseas, and because I have no mortgage.

But I watch so many of my younger friends diving into home ownership; without an existing investment portfolio; with a mortgage; and putting their entire savings into a down payment, transaction costs, and renovations. This mistake will ruin them and I wish they would do some accurate modelling before signing their lives away.

When a family looks at whether to buy or rent they generally compare just two numbers. And this is the birth of the misunderstanding. They look at the cost of renting the house over 25 years of a mortgage and the interest payments on that mortgage. If we look at a ₤1.5m home in, say, Kensington, the typical mortgage interest would be ₤730,000, whereas the rental costs would be ₤1.74m, a million more, over the same period. Families then convince themselves that they are buying an asset instead of throwing money down the drain, and saving money to boot. The mortgage is normally structured so that it is interest only in the first three years, or carries a favorable rate, so that families sign on, without grasping the financial burden to follow.

The key misunderstanding is not factoring in the opportunity costs of the income on investing those critical early savings in an income yielding, gearable, asset.

If we assume a family has carefully saved ₤600,000 to buy a house. Generally the best deals currently on offer would require proof of an income of ₤250,000 and no personal loans, which is a net take home pay of ₤144,000, in order to secure an 80% mortgage.

Buyers are sucked in by mortgage calculators that only look at the monthly payments during the 2 to 5 year fixed period, which is not a proper assessment for the costs of a 25 year mortgage. A typical website will indicate payments of just ₤5300 per month, or ₤63,750 for the year (including fees) on a ₤1,200,000 mortgage. This low rate is based on the sweet heart rate of 2.3% which will increase at refinancing. Even this ₤63,750 represents a huge 45% of net salary. But if we look at the few fixed 25 year mortgage the interest rate is 4.2% so we can assume, over the life of the mortgage that rates will normalize to this level. This means that, for the repayments to be completed by year 25 the mortgage principal will have to be ₤54,500 and then interest payments would start at ₤50,000, gradually declining. This is a completely unsustainable level of payments for a net take home pay of ₤144,000. But this is another whole discussion and reflects the likelihood, if not certainty, that the mortgage will not be paid off in a working career, and as such, the house will remain, effectively the property of the bank, through a process of continual refinancing. That aside, in the first year, they will make a down payment, on a house worth ₤1.5m, of ₤300,000. They will then pay ₤120,000 stamp duty, ₤30,000 to lawyers and surveyors, plus the first installment of the mortgage at ₤63,750. There will be two years of house decoration, maintenance, repairs, taxes, insurance and miscellaneous other expenses totaling ₤84,000. So, in two years, the ₤ 600,000 in savings are all gone and future financing and running costs will come directly from the salary.

In the first 3 years of buying a house the average family will spend 6% on decorations. Maintenance is assumed at 0.7% per year as a house generally needs to be completely overhauled every 140 years. There are then repairs (0.4%), taxes and insurance (0.3%), and other miscellaneous upkeep (0.2%) to contend with. The only difference with these costs for ‘own to let’ is the owner will only spend, on average, just 2% of the value on decorating. Otherwise all the other costs are the same.

It is important to note that in this model, if you say you have a better mortgage, better price appreciation, or lower costs, then the same adjustments made to the ‘home owner’ model need to be made to the ‘own to let’ model. The gap will remain the same. The only area that can reduce the gap modestly is that this model assumes that people have brought their home in a prime area and not in an area experiencing substantial growth over and above the mean for the city.

What the family doesn’t understand when they signed for a house at ₤1.5m was they were signing an obligation for ₤3.7m over the next 25 years. So when they proudly sell the house for ₤3.2m and move into an old people’s home, announcing to all that will listen that the house has more than doubled in value since they bought it is, in reality, an investment that lost ₤500,000 in value over the course of that time. This is because, they have signed a mortgage which will cost them a total of ₤1.9m, they will spend an average of ₤1.4m on the house, and they have no rent to offset against these costs. This includes the average single move, to reconfigure for family expansion, to a larger house in a cheaper district worth the same.

The costs quietly pile up. Families with a ₤1.5m home, will spend an average of ₤130,000 per year on mortgage payments and the other expenses of having a home compared to the renter who is ‘throwing away’ an average of ₤70,000 a year. This is the first of the 3 myths about owning a property. All those costs that owners try to forget, that keep putting demands on the cheque book. These are generally sufficiently high to ensure the family has little funds to spare for an investment portfolio any larger than a rudimentary pension plan.

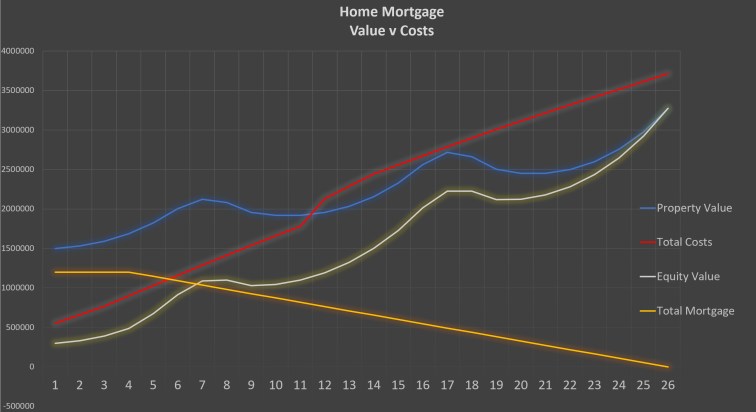

As you can see in the chart, at no point does the equity value exceed the total costs. An investment with a negative return. A financial disaster, despite the steady upward value of the property itself.

Now the two other significant differences between an ‘own to let’ and the ‘home buyer’ is that, firstly, the ‘own to let’ can choose the highest yielding sector in the fastest growing region of the country. For example the highest yielding fastest growing properties may be student housing in Inner Liverpool at 8.6% yield and 6.2% growth, rather than the lovely flat in Kensington you want to live in with a 4% yield and 3.6% growth in value.

Secondly, the ‘owner to let’ will also keep his average gearing (mortgage as a percentage of property value) close to 60% throughout the period, rather than slowly working it off. He does not need to worry about paying off his mortgage before retirement, when his salary dries up, because the portfolio is generating the income to service the loans. He is able to continually refinance because he has an income yielding asset, therefore looked on more favorably by the bank, with proof of steady rental income over the previous 12 months.

These two differences, over the 25 years, will see him with an equity holding on his initial ₤300,000 down payment worth a whopping ₤8.8m, with outstanding mortgages of ₤5.5m, so a property portfolio valued at over ₤14m! This assumes paying a management fee of 20% to deal with tenant replacement and other teething problems. He has been paying the mortgage and running costs out of his rental income so has had no further capital drawdowns from his salary. Infact total net outgoings from his savings peaked at ₤650k in Year 5 when he buys his second rental property, on which he is able to place a down payment by refinancing the first property where the equity value has increased. Net outgoings eventually turn positive in Year 19, unlike the homeowner who experiences total net outgoings of ₤3.7m.

Similarly, and even more importantly, the large portfolio will be throwing off a growing income stream every year net of all costs, at about ₤200,000 per year in Year 25 on your retirement, just at the critical time when salaries end and the tiny pension kicks in. This is a substantial pool of income as well as a meaningful asset that will be past to the next generation.

By contrast the family home owner has sold the house for a loss of ₤500,000 and moved into a smaller retirement house worth half the value. They will have to live off the capital value differential between the family home and the smaller retirement home. Towards the end they will do an Equity Release, signing their homes away to finance companies in return for an upfront payment, eventually leaving the children with nothing.

So, looking in more detail at those differences with the own to let model discussed earlier, yields in the UK vary from 3% for 3 bedroom homes in prime locations to 9% for HMO (houses with multiple occupants or bedsits). These numbers represent average rates in a growing market. Buying distressed assets overseas it is possible to get yields in the low teens but this is not available to most property buyers, and have currency risks, and sometimes additional tax costs. London’s property market is a tax lite environment, hence its appeal to foreign investors. Lets assume the ‘owner to let’ invests his money in HMO, say student bedsits in Cardiff, with a 9% yield, but lives and pays rent in a 3 bedroom prime which has a 4% yield for the owner in Kensington.

Property prices rise and fall in cycles in mature markets, so although there can be 5 years in every 10 with exciting increases of between 5% and 12% per annum, the other 5 years with small dips in value can bring the average per year, over the 25 year life of a mortgage, to an average of 4.75% rise across London per annum, with higher and lower rates in different regions. HMO will generally experience wilder fluctuations with increases and decreases about 1.5% above and below the mean.

But as you can see in the model, refinancing of the first mortgage in year 5 allows the ‘owner to let’ to buy a second property for ₤1.5m. For simplicity we assume the second mortgage is with the same bank, who has done an assessment and confirmed that the first property is now worth ₤ 1.76m and the outstanding mortgage has been paid down to ₤1.06m so the borrowers equity is now valued at ₤700k which is sufficient for an expanded mortgage of ₤2.25m allowing him to buy another block of student bedsits. This occurs again in Year 10, 14, and 21 in ever bigger purchases. After the second purchase, rental incomes now comfortably cover all costs including the rent on the home in Kensington.

In conclusion the rule of thumb then is:-

i) Do not buy a property to let which yields less than 8% or atleast 3% more than a long term fixed mortgage rate. While flexi-mortgages of 2.3% are currently available which would appear to justify a purchase with a 5.3% yield, these are short term mortgages that can be raised by the bank at the end of 2 or 3 years, with disastrous consequences. Ideally buy during a liquidity crunch and low segment of the cycle. You may have to wait 4 years for the right time. But in the meantime you can be researching segments, gather data, and continue saving more funds.

ii) Don’t buy a home until the proceeds from an investment portfolio can pay for it. NEVER use your salary.

The consequences of following these rules is a retirement with an income at least as good as you had when working, once pensions are included, and a substantial nest egg to past to the next generation.

Never forget that, while you have a home mortgage the bank ‘owns’ your property, and you are effectively paying rent to the bank. This sense of home ownership is illusory and simply condones extravagant renovation plans which you could not do in a rental apartment. Your space and location needs are constantly evolving as your job moves and children arrive. You may wish to move 4 or 5 times. Buying and selling costs are extremely prohibitive and building extensions costly restricting movements for work or suitable sizing as the third child arrives.

This single decision to play the home ownership game puts families under unnecessary and often disastrous financial stress and there is no pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. As with casinos, where everyone talks of when they won a thousand, no one talks about the many times they lost a hundred, and this encourages others to gamble their savings away.

To see the excel spreadsheet click here.

Notes

i) In a period when Central Banks are injecting US$1.5 Trillion a year into the bond and equity markets, or 3% of global GDP, rises in asset prices must not be confused with rises in value. The value of the currency pool is dropping rather than value being created in an asset class. So each pound is worth less rather than your house being worth more.

ii) In the current global environment, post 2009, and with continued QE by the ECB, we have had a decade of the lowest interest rates in 6000 years, combined with a decade of asset inflation. It is important not to assume this will continue for the next quarter century or the life of a mortgage. LIBOR has already increased 1.8% in the last 2 years indicating a tightening in the market.

You don’t blog much, but I think what you do is very good.